EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Texas judicial system is complicated, inefficient, and poorly structured to handle modern litigation. Since its basic structure was created in the late 1800s, it has been expanded periodically on a purely ad hoc basis. As a result, the system is replete with anomalies and peculiarities. Problems exist at every level and extend to the administration and funding of the courts. Comprehensive reform is needed to produce greater coherence, efficiency and accountability. This paper examines the Texas court system, the federal court system, and the court systems of other states in an effort to determine the best method for structuring, administering and financing Texas’s courts. The paper concludes with specific recommendations.

Texas’s Antiquated Court Structure

At the top of the Texas court system sit two high courts—the Supreme Court and the Court of Criminal Appeals. The Supreme Court has civil and juvenile jurisdiction. The Court of Criminal Appeals has criminal jurisdiction. Each court has nine judges. Only one other state has a similar high court structure, and no other state has this many high-court judges.

There are pros and cons to having two high courts. On one hand, operating two high courts complicates judicial-system administration. Because neither court is truly supreme, Texas’s high courts have no ability to resolve the conflicts that arise when they reach different conclusions on a point of law. On the other hand, having two high courts allows each court to bring specialized knowledge to different types of cases for the benefit of litigants. In addition, comparison to other states shows that both courts are able to consider a higher number of appeals than would be possible if there were a single high court. Ultimately, this enables each court to give greater certainty to the law by accepting cases presenting novel or complex legal issues or legal issues on which the intermediate appellate courts have disagreed.

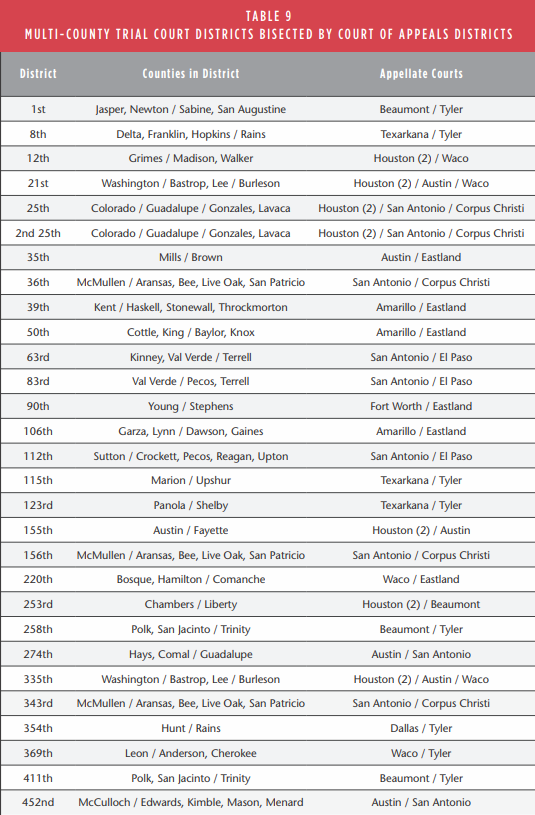

There are fourteen intermediate appellate courts in Texas whose structure and disposition of cases are complicated by overlapping geographic jurisdiction and unequal dockets. Neither the federal judicial system nor any other state’s judicial system has geographically overlapping intermediate appellate court districts. In Texas, however, the geographic jurisdiction of two intermediate appellate courts is identical and three have overlapping jurisdiction. In addition, the number of cases filed each year in the fourteen courts varies significantly. This inequality is addressed by the transfer of cases among the courts of appeals for “docket equalization”—a practice that is unpopular and unfair because a litigant cannot determine during trial which appellate court’s decisions will govern the case. A fair judicial system should have a more predictable course than a random assignment of appeals to equalize workloads between the intermediate appellate courts.

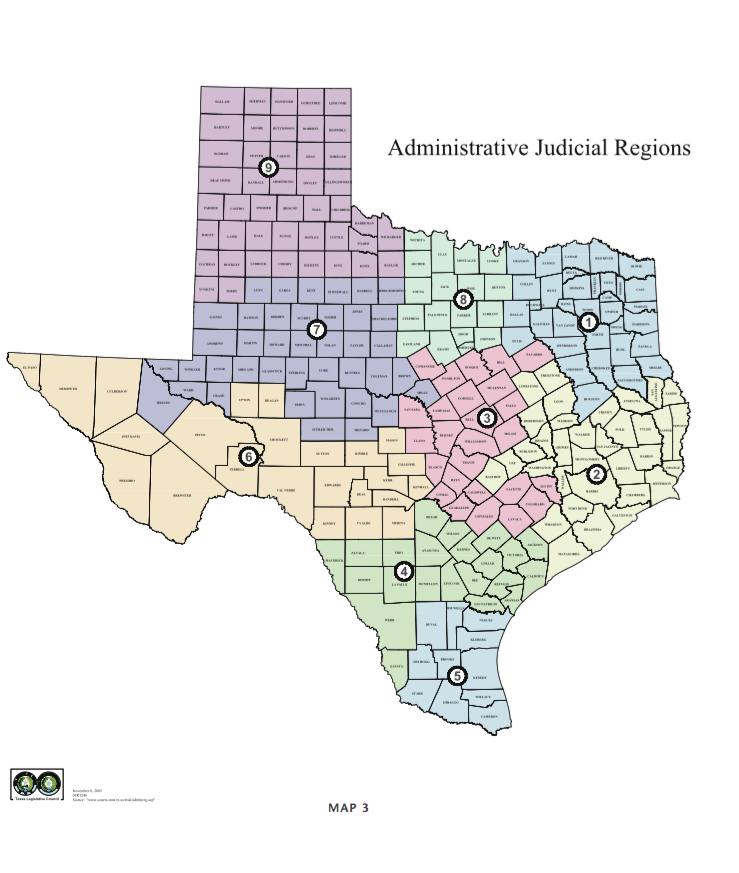

Furthermore, the assignment of district courts to the intermediate appellate courts is puzzling. Texas’s intermediate appellate court districts cut through many of its multi-county trial court districts. As a result, there are several district courts that answer to more than one intermediate appellate court. To make matters more confusing, Texas has nine administrative regions that do not coincide with the intermediate appellate court districts. And, like the appellate court districts, the administrative regions cut through multi-county trial court districts. This causes confusion and inefficiencies in the oversight of Texas courts, as will be discussed further below.

Texas has seven types of trial courts: district courts, constitutional county courts, statutory county courts, statutory probate courts, justice of the peace courts, small claims courts and municipal courts. This structure has been described by one Texas Supreme Court justice as “Byzantine” as the subject matter jurisdiction of these courts overlap substantially. In fact, the subject-matter jurisdiction of each type of trial court overlaps to some extent with the subject-matter jurisdiction of at least one other type of trial court. Moreover, the subject-matter jurisdiction of constitutional county courts and of statutory county courts varies widely from county to county. As a result of these variations, Texas’s 254 counties have almost that number of distinct trial court structures.

To complicate matters further, the district courts, which are the trial courts of general jurisdiction, sit in a spider web of districts having overlapping geographic boundaries. Often a single county is in two or three district court districts, with each of those districts being comprised of a different group of counties. This knotty trial-court structure is arcane and inefficient, and it invites forum shopping.

Among the structure’s many failings is the inability to effectively handle complex civil cases, which require significant and specialized judicial resources. While the federal court system and the court systems in other major states have special courts or procedures to handle complex or specialized litigation, Texas does not. Consequently, complex litigation in Texas often is conducted in trial courts lacking the knowledge or resources to handle that litigation.

Problems in Court Administration and Funding

Texas’s court administration system fails to provide proper control and accountability. The State is divided into nine administrative judicial regions, each with a regional presiding judge who has general responsibility for the efficient management of litigation within that region. Because the regional administrative judges are appointed by the Governor for fixed terms of office, the efficient administration of justice in these regions is not in the hands of a person who is accountable to any other judicial officer. At the local level, court administration is handled by local judges who are accountable to local officials for fiscal matters, but not really accountable to anyone other than their fellow judges for the efficient administration of justice.

Additionally, the judicial system’s funding mechanism is antiquated and uneven. Historically, many states relied predominantly on local revenues to support their courts. Many states have moved away from local funding and toward state funding in an attempt to ensure adequate funding of the court system, to facilitate the efficient administration of justice, and to enhance judicial accountability to the state supreme court. Texas, however, continues to rely heavily on locally generated revenue rather than state-generated revenue to fund its judicial system. Judicial salaries, judicial retirement, personnel, facilities, and other costs are shared by state, county and city governments. Some revenue generated by the courts are kept at the local level, while other revenue is passed through to the state government. After more than 100 years of periodic, ad hoc tinkering with the system, there is very little logic to the financial aspects of Texas’s judicial system.

Past Reform Efforts

These and other peculiarities of Texas’s judicial system have given rise to numerous calls for reform. The reform movement started as early as 1918, when the Texas Bar Association adopted a proposal to replace the judicial article of the Texas Constitution, Article V, with a new judicial article. The new judicial article, according to one commentator, “embodied the principles of unification, flexibility of jurisdiction and assignment of judicial personnel, and responsible supervision of the entire system by the supreme court.” That effort failed. A number of additional efforts to rewrite Article V have been attempted since 1918 with no success. The recurring themes of these reform efforts were eliminating the two-high-court structure by merging the Court of Criminal Appeals into the Texas Supreme Court, providing a coherent system of judicial administration by the Supreme Court, giving criminal jurisdiction to the intermediate appellate courts, structurally unifying Texas’s trial courts, and implementing a method other than partisan elections for selecting judges.

While Article V has not been redrafted, some progress has been made toward these reform goals. By constitutional amendment effective September 1, 1981, Texas’s intermediate appellate courts were given criminal jurisdiction (except in death penalty cases), and a number of justices were added to those courts to handle the additional work. At the same time, the Court of Criminal Appeals’ jurisdiction was made discretionary. The constitutional amendments also confirmed the Supreme Court’s inherent power over the judiciary, and, since 1981, the Legislature has created a statutory scheme giving the Supreme Court a good deal of administrative control over the judiciary. Unfortunately, however, Texas’s trial court structure has become more, rather than less, fragmented and inconsistent since 1981.

Recommendations

This paper provides methods of improving Texas’s court system. After thoroughly discussing Texas’s courts and other court systems, it provides the following recommendations and proposals for reforming the structure, administration and financing of Texas’s courts.

- Study merging Texas’s two high courts into a single court having both civil and criminal jurisdiction.

- Reduce the number of judges on both the Texas Supreme Court and the Court of Criminal Appeals from nine to seven judges if the two courts are not merged.

- Give the Texas Supreme Court discretionary jurisdiction in all civil appellate matters.

- Reduce the number of intermediate appellate courts, subject to complying with the federal Voting Rights Act, which this paper does not address.

- Eliminate overlapping geographic boundaries among the intermediate appellate courts. Again, redistricting of the appellate courts must take into account the Voting Rights Act, which this paper does not address.

- Allow the Chief Justice of the Texas Supreme Court, rather than the Governor, to appoint and remove regional administrative judges.

- Repeal the current legislative requirement that the Supreme Court transfer cases from one intermediate appellate court to another for docket equalization.

- Structurally unify the trial courts into a single-tier structure, however, it may not be practical or necessary to merge the municipal courts into the single tier of trial courts.

- Make the following changes in Texas’s trial court structure even if complete rationalization is not adopted:

- Convert the statutory county courts at law and statutory probate courts into district courts.

- Remove judicial authority from those constitutional county courts sitting in counties having a statutory county court at law or a district court sitting only in that county.

- Redraw district court boundaries to eliminate overlapping districts and ensure that each district court is in a single court of appeals district and a single administrative region.

- Increase the amount-in-controversy threshold for district courts’ civil jurisdiction to $10,000.

- Increase justice of the peace court jurisdiction to allow adjudication of civil disputes with $10,000 or less in controversy.

- Provide for district court jurisdiction of commercial eviction cases in which the amount in controversy exceeds the jurisdictional limit of the justice of the peace courts.

- Eliminate the current small claims courts (i.e., the justice of the peace sitting as a “small claims” judge), but direct the Supreme Court to promulgate rules for the expeditious handling of small civil matters.

- Establish a mechanism for moving complex cases to trial courts having the expertise and resources to handle those complex cases, as follows:

- Convert the currently existing Multidistrict Litigation Panel into the Complex and Multidistrict Litigation Panel (CMDL Panel).

- Give the CMDL Panel power to transfer complex cases to trial judges having the knowledge and resources to handle complex litigation while retaining the MDL Panel’s current power to transfer large numbers of factually similar cases (“multidistrict cases”) to a single trial judge for pretrial proceedings.

- Instruct the Supreme Court to define “complex case” but provide statutory guidance on the definition.

-

- Require the Texas Supreme Court to promulgate rules governing the CMDL Panel’s work, setting out the definition of “complex case,” distinguishing between “complex cases” and “multidistrict cases” and providing special rules for each, and providing the procedure for requesting and attaining the transfer of a complex case by the CMDL Panel.

- Provide that complex cases (but not multidistrict cases) must be assigned to a trial court in the court of appeals district in which the case was originally filed (assuming it was a county of proper venue).

- Provide that the trial judge may conduct pre-trial proceedings in his or her court, or in any appropriate court in the court of appeals district.

- Provide that the judge of a court to which a complex case is assigned (but not the judge assigned to a multi-district case) must return with the case to the county in which it was originally filed (assuming it was a county of proper venue) for trial.

- Appropriate funds to support the CMDL Panel and the selected trial courts sufficient for them to employ professional and administrative staff to handle the transfer process, pre-trial proceedings and the trial of complex cases themselves.

- Fund Texas’s trial courts primarily from State, rather than local, revenue.

- Continue to increase judicial compensation, so that Texas’s judges are compensated at a level comparable to other populous states and appropriate to the importance of their work.

The efficient administration of justice in this state depends on a modern court structure. Texas is long overdue for reform to its court system. The goal of this paper is to produce thought and discussion about the Texas judicial system to aid policy-makers as they consider and act on the recommendations offered here.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INDEX OF CHARTS, MAPS AND TABLES

INTRODUCTION

TEXAS COURT STRUCTURE

Overview

High Courts

Creating Two High Courts

Supreme Court of Texas

Number of Justices and Terms of Office

Jurisdiction

Workload

Supervising the Judiciary

Court of Criminal Appeals

Number of Judges and Terms of Office

Jurisdiction

Workload

Intermediate Appellate Courts

History of Texas’s Intermediate Appellate Courts

Courts of Appeals Today

Judges and Districts

Jurisdiction

Workload

Trial Courts

1876 Trial Court Structure

Today’s Byzantine Trial Court Structure

District Courts

Number of Courts and Qualification of Judges

Jurisdiction

Districts and Reapportioning Districts

Workload

County-Level Courts

Statutory County Courts (County Courts at Law)

Statutory Probate Courts

Constitutional County Courts

Workload of the County-Level Courts

Justice of the Peace Courts

Small Claims Courts

Municipal Courts

TEXAS COURT ADMINISTRATION, JUDICIAL PAY, AND COURT FUNDING

Overview

Administration

Supreme Court’s Administrative Duties

Court of Criminal Appeals’ Administrative Duties

Regional Administration

Local Administration

Texas Judicial Council

Office of Court Administration

Judicial Pay and Retirement

Court Funding

Judicial System Revenues

Judicial System Expenditures

OTHER JUDICIAL SYSTEMS

Overview

Structure

Federal Courts

Article III Courts

Tribunals Adjunct to District Courts

Article I Courts

State Courts

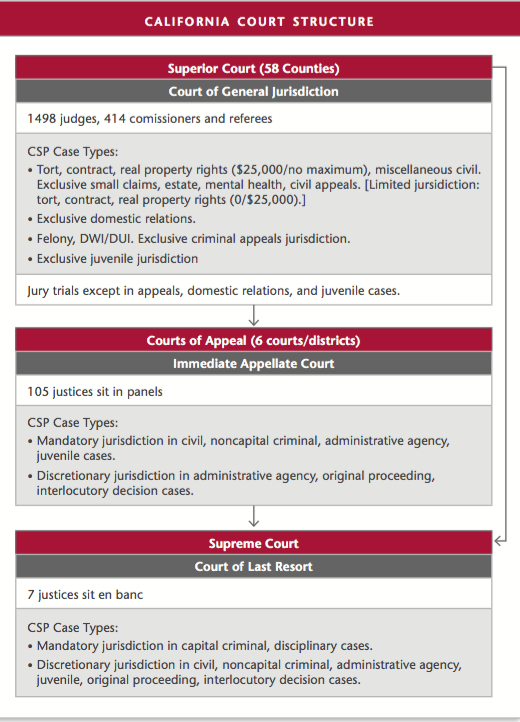

California

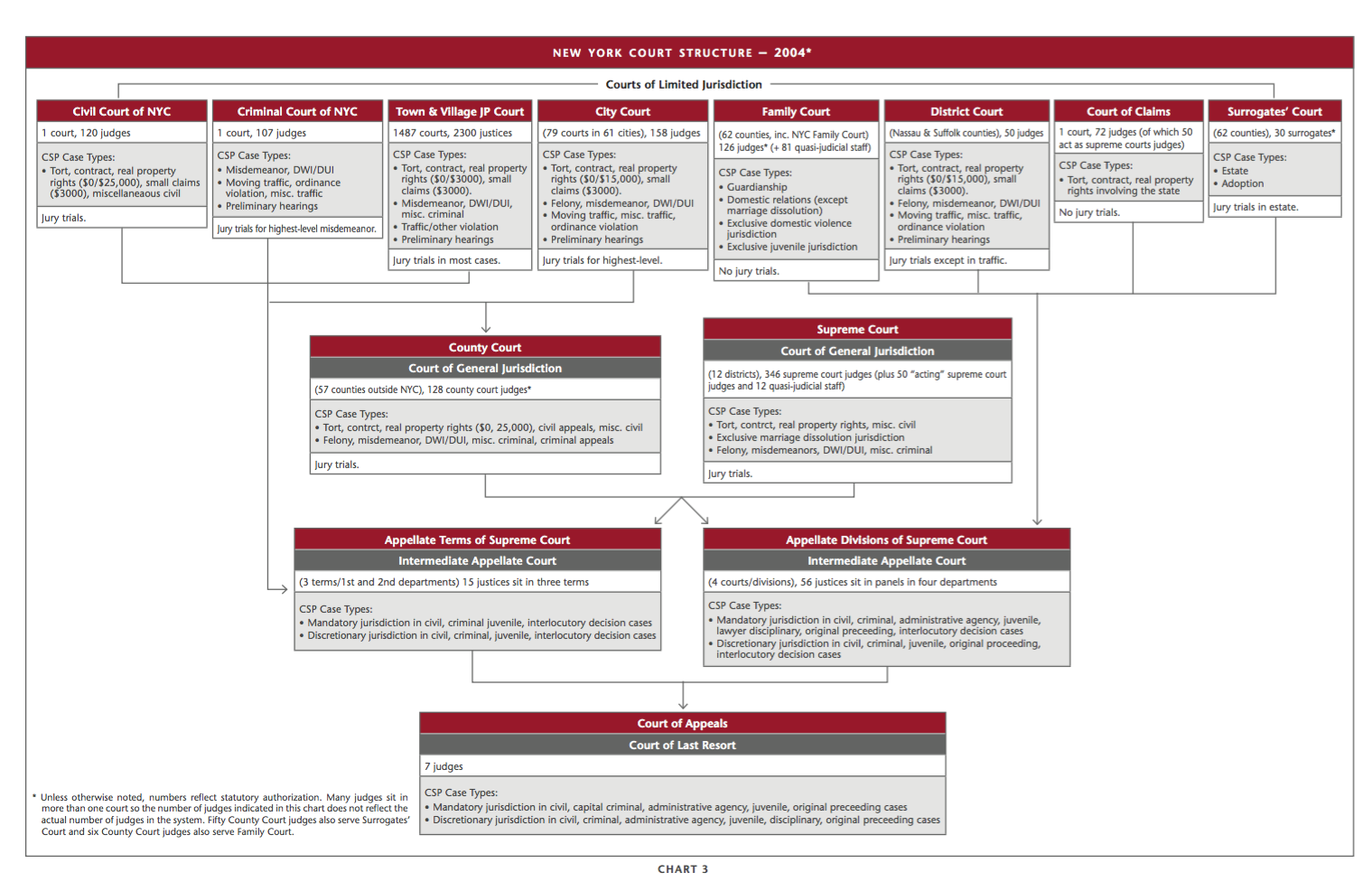

New York

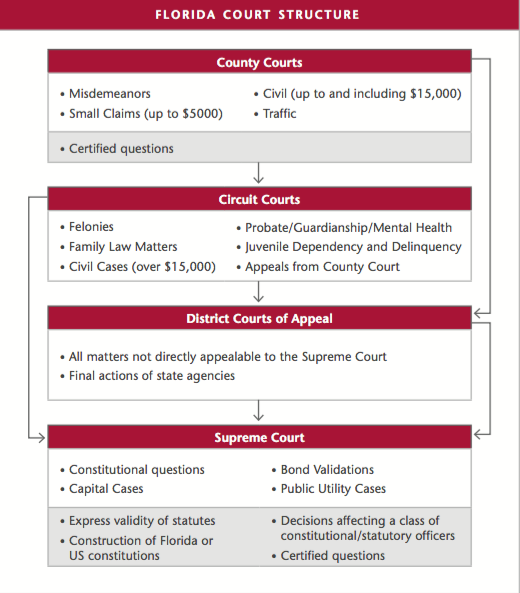

Florida

Other States

Court Administration

Federal Courts

State Courts

California

New York

Florida

Judicial Pay

Funding and Budgeting

Federal Courts

State Courts

Complex or Business Litigation Courts

Federal Courts

State Courts

Complex Litigation Courts

Business Litigation Courts

Commercial Litigation Courts

RESTRUCTURING, ADMINISTERING AND FUNDING TEXAS COURTS

Overview

Possible Structural Changes

Supreme Court and Court of Criminal Appeals

Introduction

Merge the Two High Courts?

Consistency in Decisions

Lack of Voter Knowledge

Administrative Efficiency

Opportunity for Review

Judicial Expertise

Acceptance by the Bar

Need for Constitutional Amendments

Reduce the Number of Judges on the Two High Courts?

Give the Supreme Court Discretionary Jurisdiction in All Matters? 4

Courts of Appeals

Introduction

Reduce the Number of Courts of Appeals?

Eliminate Overlapping Courts of Appeals Districts?

Prohibit Docket Equalization Transfers?

Trial Courts

Introduction

Should the Trial Courts be Structurally Unified?

Better Use of Judges

Tighter Management Structure

Case Management

Staffing Efficiencies

Record Systems and Automation

Are There Steps Short of Unification to Rationalize the System?

Convert the County Courts at Law and Probate Courts into District Courts

Redistrict the District Courts

Create a Mechanism for Handling Complex Cases

Increase the Threshold for District Court Jurisdiction

Remove Judicial Authority from Some Constitutional County Courts

Eliminate Small Claims Courts

Increase the Maximum Civil Jurisdiction of Justice of the Peace Courts

Provide for District Court Jurisdiction of Larger Commercial Eviction Cases and for a Right of Appeal

Synopsis of Changes

Possible Administrative and Financial Changes

Court Administration

Financial Matters

Should State Revenue be the Exclusive Source of Funds for the Texas Judicial System?

Should Compensation of Judges Be Increased?

CREATING COMPLEX LITIGATION COURTS

Introduction

Selecting the Court or Judge

Kinds of Cases the Courts Could Handle

Other States’ Definitions of “Complex Case”

Defining “Complex Litigation” if New Courts are Created

Defining “Complex Litigation” if Existing Courts are Used

First Alternative

Second Alternative

Number of Courts Needed if New Courts are Created

Geographic Scope of Complex Litigation Courts

Venue Considerations

Texas’s Venue Scheme

Venue Considerations for Complex Courts

Juries in Complex Litigation Cases

Filing in or Transferring to Complex Litigation Courts

Moving Cases if Existing Courts are Used

Filing or Transferring Cases if New Courts are Created

Costs Associated with New Complex Litigation Courts

Synopsis & Recommendation

CONCLUSION

Appendices

INDEX OF CHARTS, MAPS AND TABLES

CHART 1 Texas Court Structure – 2006

TABLE 1 Courts of Appeals Years of Establishment

MAP 1 Courts of Appeals Districts

TABLE 2 Per-Judge Filings in Courts of Appeals

TABLE 3 Transfers for Docket Equalization (2005)

TABLE 4 Texas Court Structure 1876

TABLE 5 Texas Court Structure 2006

TABLE 6 District Court Jurisdiction

MAP 2 Current State District Courts

TABLE 7 County Court at Law Jurisdiction

TABLE 8 Probate Court Jurisdiction

TABLE 9 Constitutional County Court Jurisdiction

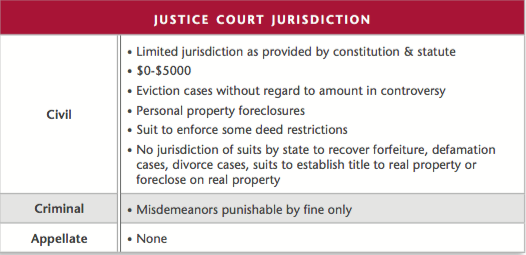

TABLE 10 Justice Court Jurisdiction

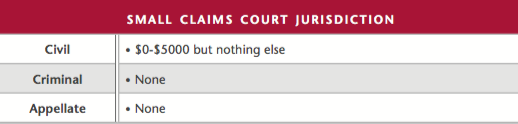

TABLE 11 Small Claims Court Jurisdiction

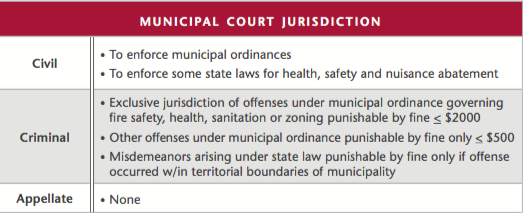

TABLE 12 Municipal Court Jurisdiction

MAP 3 Administrative Judicial Regions

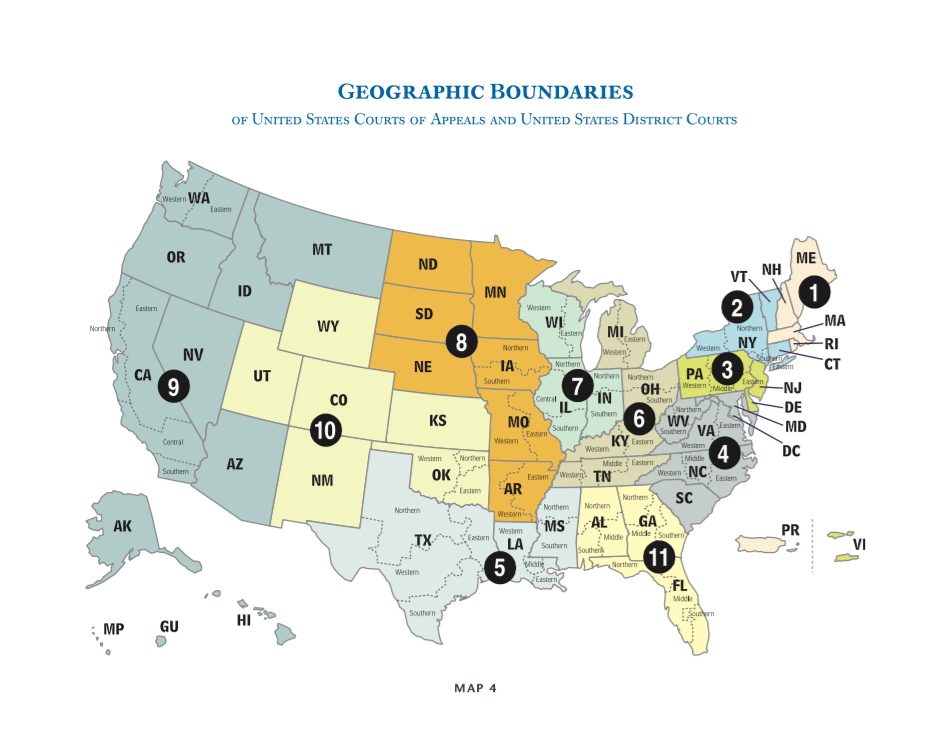

MAP 4 United States Courts of Appeals and District Courts

CHART 2 California Court Structure

CHART 3 New York Court Structure, 2004

CHART 4 Florida Court Structure

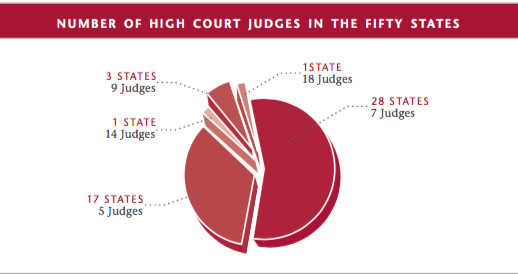

CHART 5 Number of High Court Judges in the Fifty States

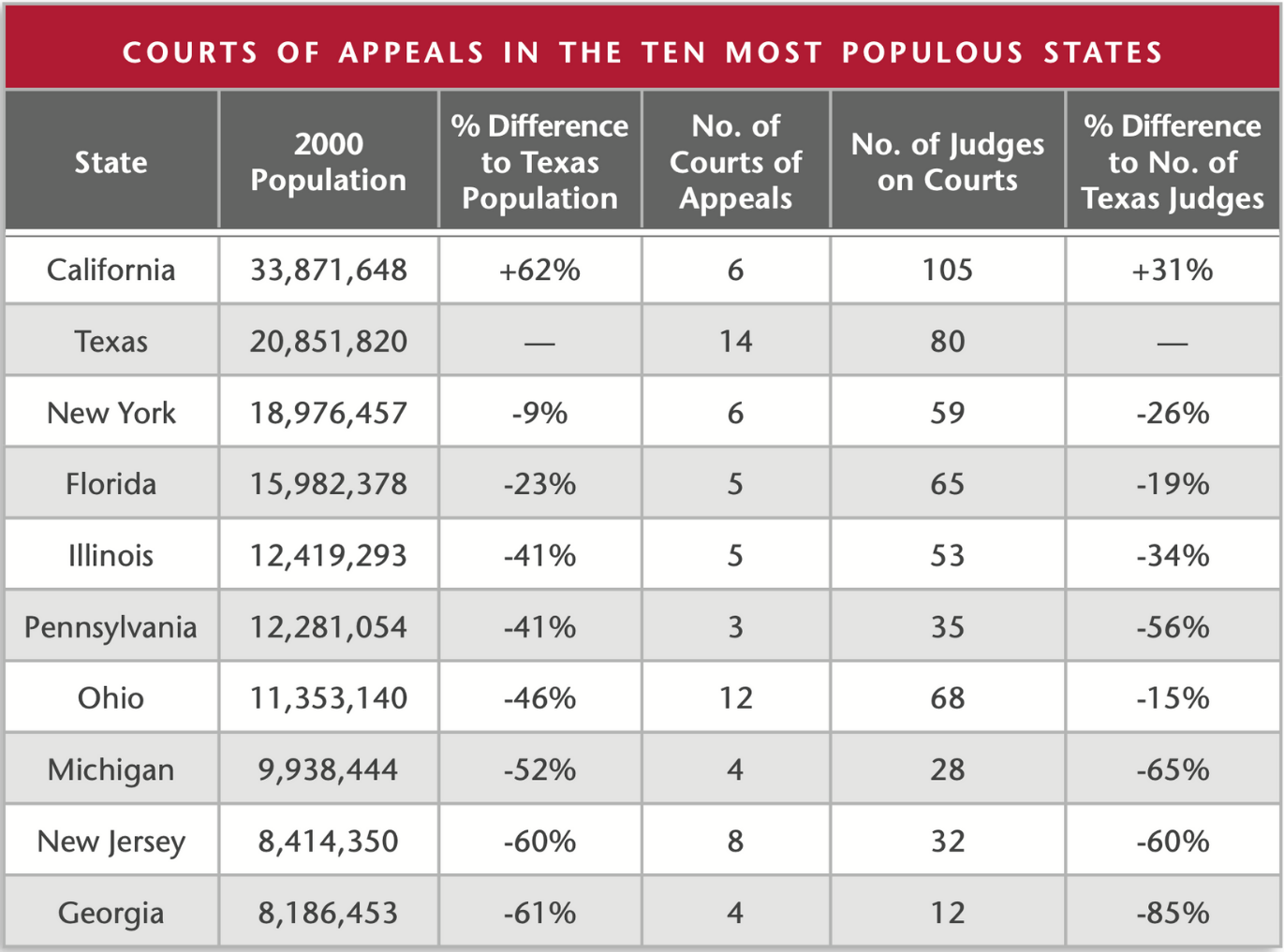

TABLE 13 Courts of Appeals in the Ten Most Populous States

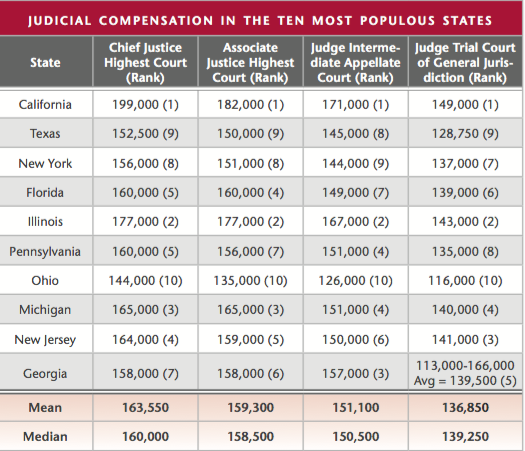

TABLE 14 Judicial Compensation in the Ten Most Populous States

Texas Judicial System: Subject-Matter Jurisdiction of the Courts

APPENDIX 1

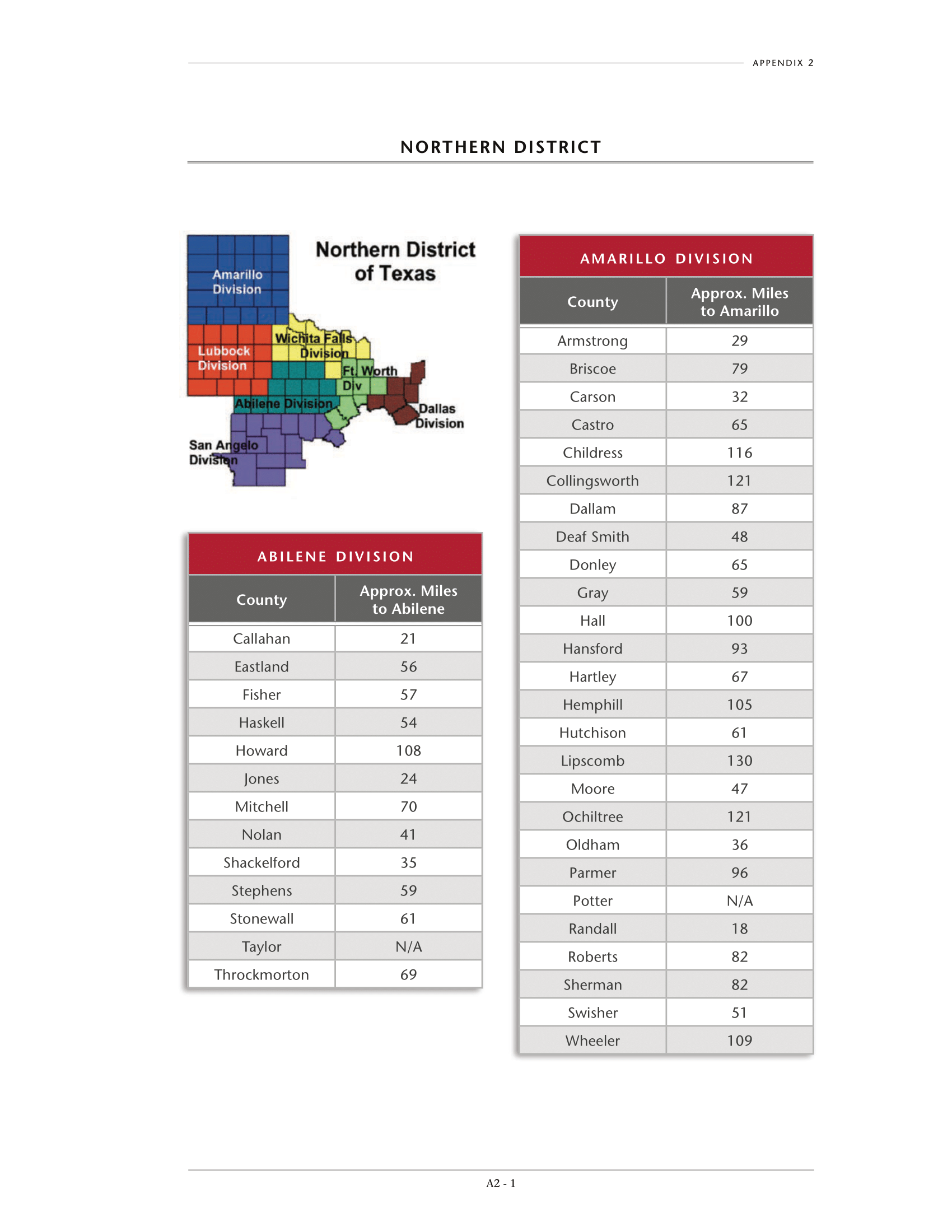

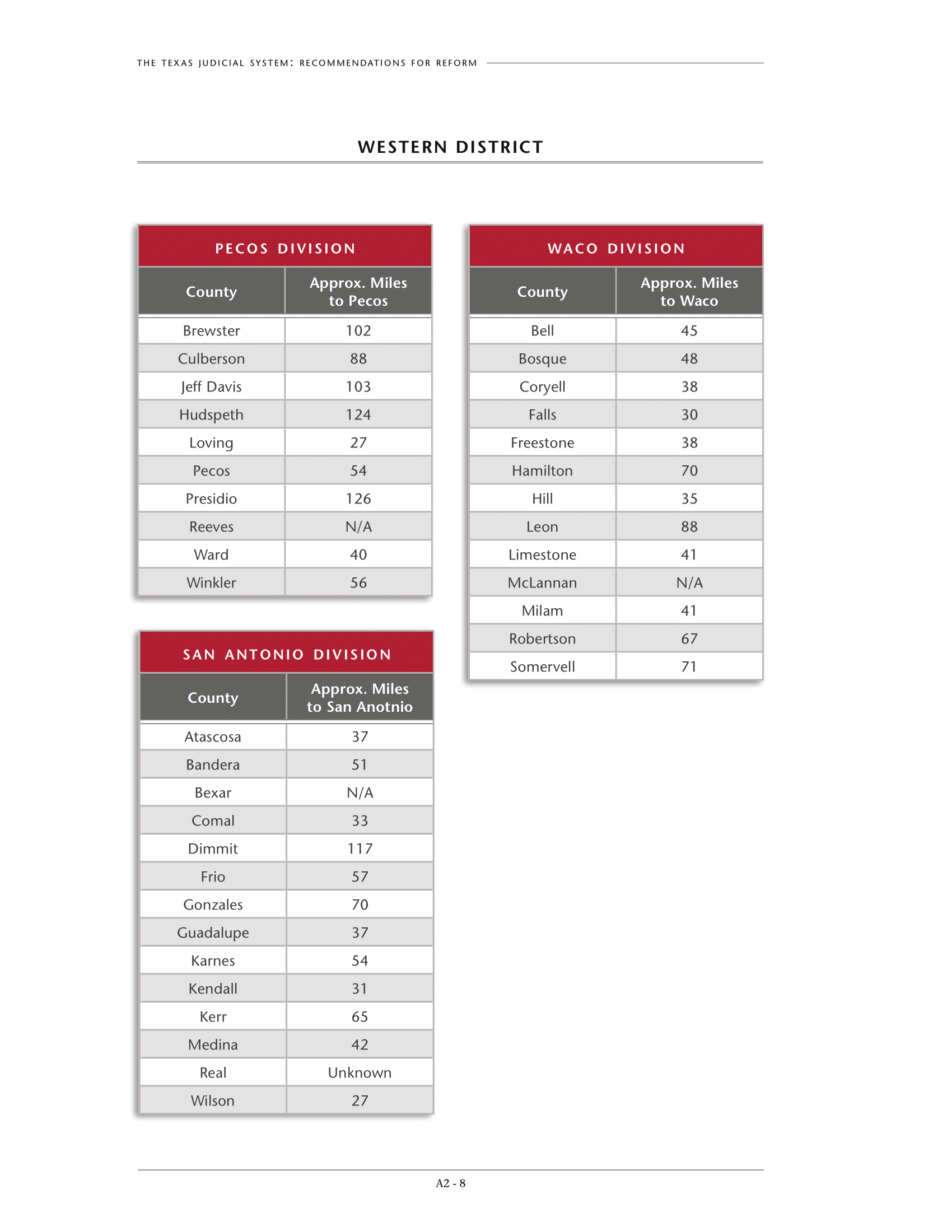

Federal District Courts in Texas

APPENDIX 2

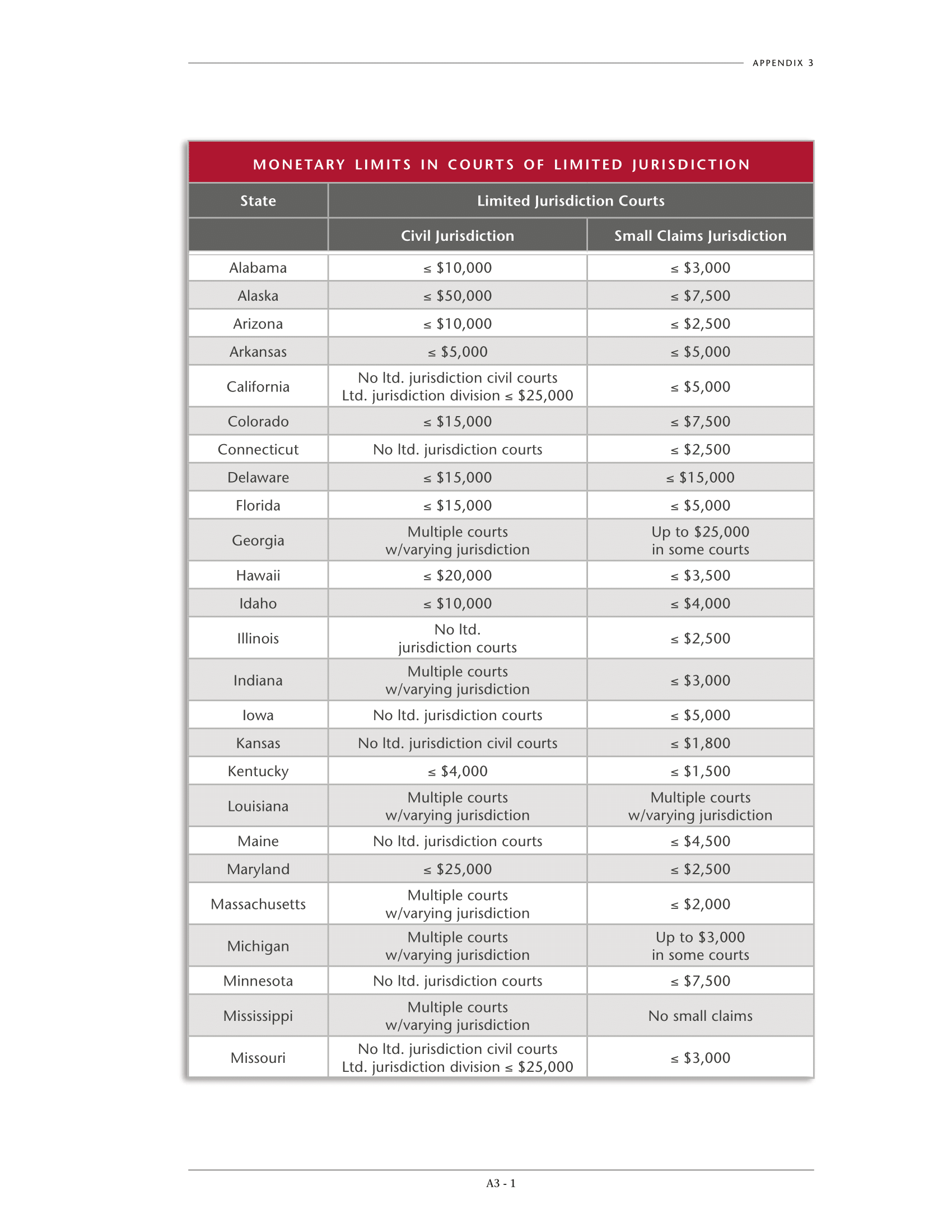

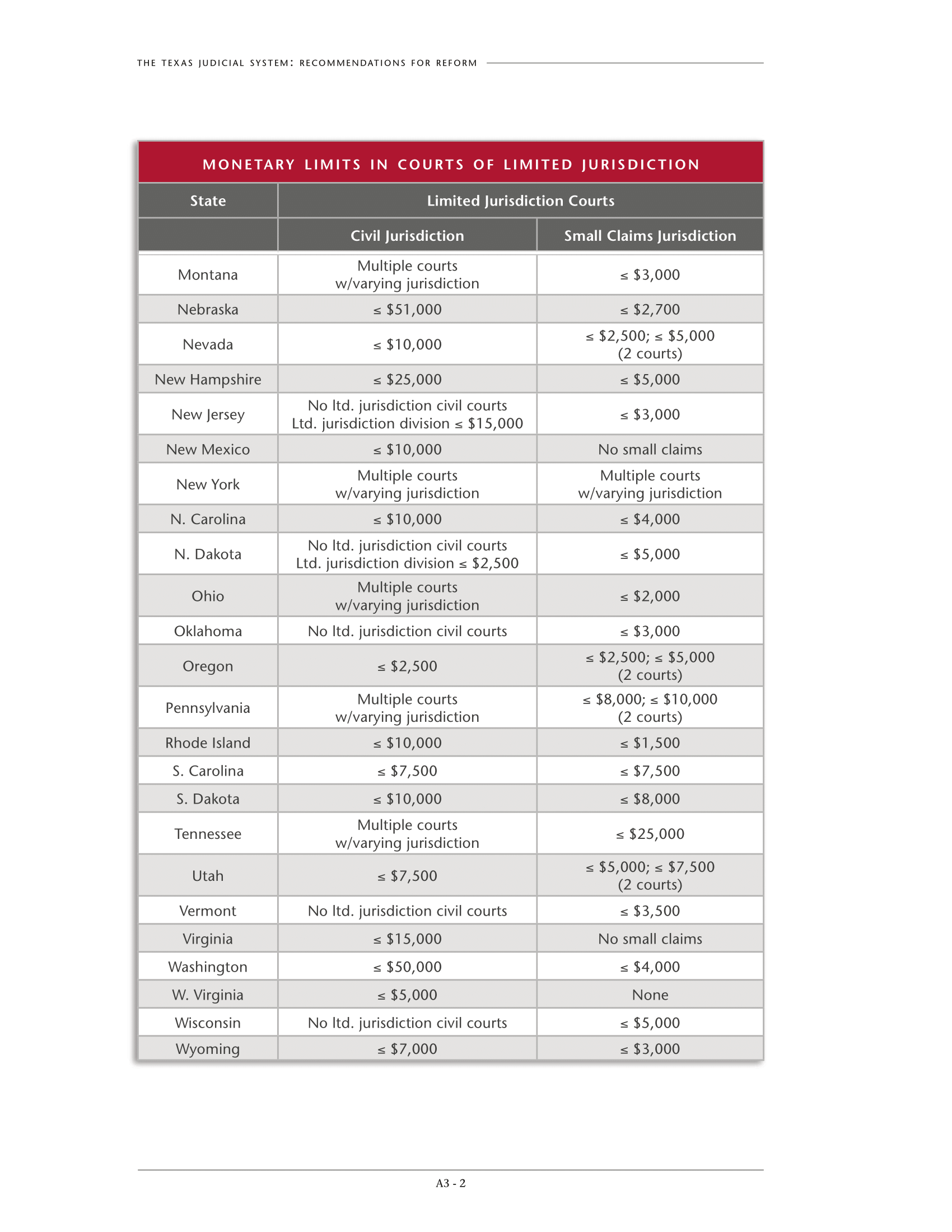

Monetary Limits in Courts of Limited Jurisdiction

APPENDIX 3

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to analyze the structure, funding and administration of Texas’s courts with the goal of recommending changes to improve the courts’ ability to meet the challenges of modern litigation. Pages 3-34 of the paper give a detailed description of Texas’s court structure, focusing primarily on each court’s geographic and subject-matter jurisdiction. Pages 35-50 describe Texas’s system for supervising and funding its courts. For comparison, Pages 51-70 provide an overview of the structure, administration, and funding of other court systems, with particular attention given to the federal, California, New York and Florida court systems. Also included in this section is a review of how other states handle specialized or complicated litigation. Pages 71-92 make recommendations for changing Texas’s court system, including reducing the number of judges on the State’s two high courts from nine on each court to seven, reducing the number of intermediate appellate courts, eliminating the transfer of cases between the intermediate appellate courts for docket equalization, redistricting certain trial courts, merging several layers of trial courts, establishing uniform jurisdiction among the trial courts, creating a system for assigning complex cases to appropriate trial courts, allowing the Supreme Court to appoint administrative judges, conforming administrative judicial districts with the courts of appeals districts, and requiring the State to assume the primary obligation of funding the judiciary. Pages 93-104 describe the alternative methods the Legislature could use to create a system for assigning complex litigation to courts having the resources and knowledge to handle those cases, and culminates in a specific recommendation.

TEXAS COURT STRUCTURE

Overview

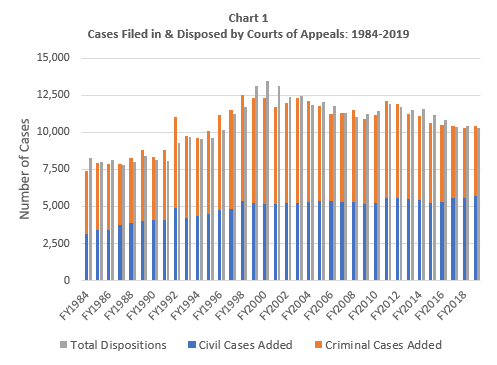

Article V, § 1 of the Texas Constitution provides that the “judicial power of this State shall be vested in one Supreme Court, in one Court of Criminal Appeals, in Courts of Appeals, in District Courts, in County Courts, in Commissioners Courts, in Courts of Justices of the Peace, and in such other courts as may be provided by law.”1 The Texas judicial system consists of two high courts, the Supreme Court and the Court of Criminal Appeals, with nine members each;2 fourteen intermediate courts of appeals with a total of eighty justices;3 432 operating district courts;4 254 constitutional county courts;5 217 operating statutory county courts;6 seventeen operating statutory probate courts;7 municipal courts sitting in 912 cities with a total of 1396 judges;8 and 825 justice of the peace courts (Chart 1).9

CHART 1

High Courts

Creating Two High Courts. Since the formation of the Republic of Texas in 1836, Texas’s constitutions have vested the State’s judicial power in “one supreme court.”10 The Supreme Court’s geographic jurisdiction always has been statewide, and the Court always has had appellate subject-matter jurisdiction.

During the time Texas was a republic, the Texas Supreme Court had appellate jurisdiction in both civil and criminal matters.11 Texas joined the United States in 1845 and adopted a new constitution, which provided that the Supreme Court’s criminal jurisdiction was subject to “such regulations as the Legislature shall make.”12 Subsequent constitutions continued to restrict, or allowed the Legislature to restrict, the Supreme Court’s criminal jurisdiction.13

The 1876 constitution removed all criminal jurisdiction from the Supreme Court and placed that jurisdiction in “a Court of Appeals” consisting of three judges having the same qualifications as Supreme Court justices.14 The Court of Appeals was given appellate jurisdiction of “all criminal cases, of whatever grade, and in all civil cases…of which the County Courts have original or appellate jurisdiction.”15 The Supreme Court remained the court of last resort for other civil matters.

In 1891, the constitution was amended to provide for a Supreme Court having civil but not criminal jurisdiction, and for a Court of Criminal Appeals having criminal but not civil jurisdiction.16 The intermediate appellate courts’ jurisdiction was limited to civil cases.17 Thus, after ratification of the 1891 amendments, Texas had two high courts, with one having civil jurisdiction and the other having criminal jurisdiction. That structure remains in place today.18

In 1980 (effective September 1, 1981), the constitution was amended to give the intermediate courts of appeals criminal jurisdiction except in death penalty cases, which are provided a direct appeal-of-right to the Court of Criminal Appeals. The amendments also gave the Court of Criminal Appeals discretionary jurisdiction to review the intermediate appellate courts’ judgments in criminal cases.19

Only Texas and Oklahoma have two high courts.20 Like Texas, Oklahoma allocates civil jurisdiction to its supreme court and criminal jurisdiction to its court of criminal appeals.21 The federal system and all other states’ systems have a single high court having both civil and criminal jurisdiction.22 With nine judges on each of its high courts, Texas has the highest number of high-court judges in the United States.23

Supreme Court of Texas

Number of Justices and Terms of Office. The Supreme Court of Texas is comprised of a Chief Justice and eight justices, each of whom serves a six-year term.24 To be eligible to serve on the Supreme Court, a person must be licensed to practice law in Texas, a citizen of the United States and of Texas, at least thirty-five years of age, and, as of the date of election, must have been a practicing lawyer, or a lawyer and judge of a court of record, for at least ten years.25 The justices’ terms rotate so that, in the normal course, three seats on the Court are filled each election cycle26 in statewide, partisan elections.27 Mid-term vacancies are filled by gubernatorial appointment with the consent of the Senate until the next succeeding general election, at which time the voters fill the vacancy for the unexpired term.28

Jurisdiction. The Texas Supreme Court has statewide jurisdiction in civil cases, including juvenile delinquency cases.29 It does not have jurisdiction in criminal cases.30 The specific contours of the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction, however, are somewhat complicated.

In discussing the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction, it is necessary to distinguish between final judgments and interlocutory trial court orders. A final judgment is one that disposes of all claims by all parties.31 An interlocutory trial court order is one that resolves at least one particular issue, but does not dispose of all claims by all parties (for example, an order granting or denying a request to postpone trial).32 The general rule in Texas is that an appeal is available in a civil case if the trial court has rendered a final judgment; but an appeal is not available to obtain review of most interlocutory trial court orders unless a statute makes the order appealable.33

In regard to final judgments, the Texas Supreme Court has jurisdiction to hear an appeal from any final judgment rendered by a Texas trial court in a civil case, except those judgments that are not appealable because the amount in controversy is too small.34 All appeals from final judgments must be presented to and decided by the appropriate intermediate appellate court before the appeal can be advanced to the Texas Supreme Court.35 The Court has the power to review any case “in which it appears that an error of law has been committed by the court of appeals, and that error is of such importance to the jurisprudence of the state that, in the opinion of the supreme court, it requires correction.”36 This provision effectively gives the Supreme Court discretionary jurisdiction in civil cases in which a final judgment has been rendered because the Court is the sole arbiter of whether a case presents an error of law important to the State’s jurisprudence.

In regard to interlocutory trial court orders, the Court’s jurisdiction is limited. The court has jurisdiction to hear an appeal from a trial court order granting or denying an injunction on the ground of the constitutionality of a Texas statute, and that appeal may be taken directly from the trial court to the Texas Supreme Court.37 The Supreme Court also has jurisdiction to hear an appeal from a trial court order (1) certifying or refusing to certify a class, (2) denying a summary judgment to a media defendant who asserts a defense under the free speech or free press clauses of the First Amendment, or (3) denying a defendant’s motion relating to a plaintiff’s failure to file an expert report, or an adequate expert report, in a medical malpractice case.38 These appeals must go through the court of appeals before being advanced to the Supreme Court.

Otherwise, the Supreme Court does not have jurisdiction to hear an appeal from an interlocutory trial court order unless the order is appealable by statute39 and either: (1) a dissenting opinion was handed down in the case by a justice of the court of appeals (known as “dissent jurisdiction”), or (2) the court of appeals’ decision conflicts with the prior decision of another court of appeals or the Supreme Court (known as “conflict jurisdiction”).40 Because dissenting opinions are rare and conflict jurisdiction historically has been difficult to establish,41 the court of appeals’ decision cannot be reviewed by the Supreme Court in most appeals taken from interlocutory trial court orders.

Whether it is an appeal from a final judgment or an appeal from an interlocutory trial court order, the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction is limited to resolving questions of law.42 The courts of appeals’ judgments are “conclusive on the facts” of the case.43 In other words, if there is a conflict in the facts presented, the Supreme Court is prohibited from ruling that the lower court erred in the way it resolved that conflict.44

The Texas Supreme Court or a justice of the Supreme Court has the power to issue writs “agreeable to the principles of law regulating those writs, against a statutory county court judge, a statutory probate court judge, a district judge, a court of appeals or a justice of a court of appeals, or any officer of state government except the governor, the court of criminal appeals, or a judge of the court of criminal appeals.”45 Additionally, the Supreme Court is the only Texas court having authority to issue a mandatory or compulsory writ of process against any of the officers of the executive departments of Texas government to compel the performance of a judicial, ministerial, or discretionary act or duty that, by state law, the officer is authorized to perform.46 Finally, the Texas Supreme Court has jurisdiction to answer questions of state law certified to it by a federal appellate court.47

Workload. Appeals are taken to the Texas Supreme Court by petition for review.48 Over the past ten years, the Supreme Court has received, on average, 964 petitions for review each year.49 In addition, it has received, on average, 2057 other filings requiring court action, including petitions for extraordinary writs and extraneous motions.50 The number of petitions for review received each year has been decreasing since peaking in fiscal year 2000, when 1069 petitions were filed.51 In fiscal year 2005, 805 petitions for review were filed, a number 25% below the high established in 2000 and 16% below the ten-year average.52 Over the past ten years, the Court has granted an average of 110 petitions for review each year, or 11% of the number disposed.53 In fiscal year 2005, it granted 109 of the 823 petitions disposed, or 13%.54 The Court hands down an average of 162 opinions per year, or roughly eighteen opinions per judge per year.55

Supervising the Judiciary. While the Texas Constitution, like the United States Constitution, provides for “one supreme court,”56 several aspects of Texas’s judicial structure prevent the Texas Supreme Court from being a true supreme court. For example, the Texas Supreme Court is given administrative and supervisory control over the judicial branch.57 Thus, the Supreme Court appears to have administrative and supervisory authority over all Texas courts, including the State’s other high court. In reality the Supreme Court has not exercised supervisory control over the Court of Criminal Appeals and it shares its administrative duties with that court and with regional and local judges over whom it has little control.58 Accordingly, no court in Texas exercises true administrative control over the entire judicial system like the United States Supreme Court exercises over the federal system, or many state supreme courts exercise over their respective states’ judicial systems.

Similarly, the Supreme Court has the power to promulgate rules of procedure and of evidence, but so does the Court of Criminal Appeals.59 The two courts have chosen to cooperate in the promulgation of the rules of evidence and appellate procedure, but there are instances where the rules differ in civil and criminal cases because the courts did not agree on a single rule and neither court has the authority to craft a rule applicable to all cases.60

Additionally, the Texas Supreme Court, as we have noted, is the only Texas court with the authority to issue a mandatory or compulsory writ of process against an officer of the executive branch of Texas government,61 but it has no such authority over the Court of Criminal Appeals, and vice versa.62

Furthermore, the Supreme Court has no jurisdiction to review decisions made by the Court of Criminal Appeals, and the Court of Criminal Appeals has no jurisdiction to review decisions made by the Supreme Court.63 While each court may consider the other’s opinion on a point of law, neither is bound by the other court’s precedent. This produces both consistent64 and inconsistent65 decisions by the two courts and because neither court has jurisdiction to hear an appeal from the other court, conflicts between the two courts on matters of state law cannot be cured by any Texas court. This peculiar situation is unique to Texas and Oklahoma.66

Court of Criminal Appeals

Number of Judges and Terms of Office. The Court of Criminal Appeals is comprised of a presiding judge and eight judges, each serving a six-year term.67 Court of Criminal Appeals judges must have the same qualifications as Supreme Court justices.68 As with the Supreme Court, the judges’ terms rotate so that in the normal course three seats on the Court are set for election during each election cycle.69 The judges are elected in statewide, partisan elections.70 Mid-term vacancies are filled by gubernatorial appointment with the consent of the Senate until the next succeeding general election, at which time the voters fill the vacancy for the unexpired term.71

The Court may sit in panels of three judges “for the purpose of hearing cases,” but typically does not do so; instead, the court routinely sits en banc when hearing appeals.72 The Presiding Judge must convene the court en banc for the transaction of all other business, including proceedings involving capital punishment.73

Texas law allows the presiding judge to appoint individual commissioners to aid the Court in its work.74 In addition, the Court may appoint a commission to aid the Court in disposing of the business before the Court.75 The opinions of the commission or of a commissioner, when approved by the Court, have the same weight and legal effect as an opinion handed down by the Court itself.76 These provisions for appointing individual commissioners and a commission were used when the intermediate courts of appeals did not have criminal jurisdiction and, because the Court had a non-discretionary obligation to hear all criminal appeals, the Court had a substantial backlog of pending cases.77

Jurisdiction. The Court has final appellate jurisdiction in all criminal cases appealed from state courts throughout Texas.78 In cases in which the death penalty has been assessed, the only appeal in the Texas state-court system is to the Court of Criminal Appeals, which must hear the case.79 The appeal of all other criminal cases is to the appropriate court of appeals, with the Court exercising its discretion to review decisions of the courts of appeals.80

The Court and each of its judges acting individually have the power to issue writs of habeas corpus and other appropriate writs.81 Additionally, the Court has jurisdiction to answer questions of state law certified to it by a federal appellate court.82

Workload. Over the past ten years, the Court of Criminal Appeals has received, on average, 313 direct appeals; 6236 applications for writ of habeas corpus; 702 petitions in original proceedings; and 2080 petitions for discretionary review.83 Thus, it receives an average of 7251 filings each year that it must review and 2080 filings that it has discretion to review.84 It has handed down, on average, 628 opinions per year, or about seventy opinions per judge per year.85 On average, the Court has granted petitions for discretionary review at a rate of about 7% of the number of petitions disposed.86 The Court’s rate of granting petitions for discretionary review over the past five years, 6.4%, has been lower than its ten-year average.87

The Court of Criminal Appeals, like the Supreme Court, has administrative duties, but, as is discussed on Pages 37-38, it does not have as many such duties as the Supreme Court.88

Intermediate Appellate Courts

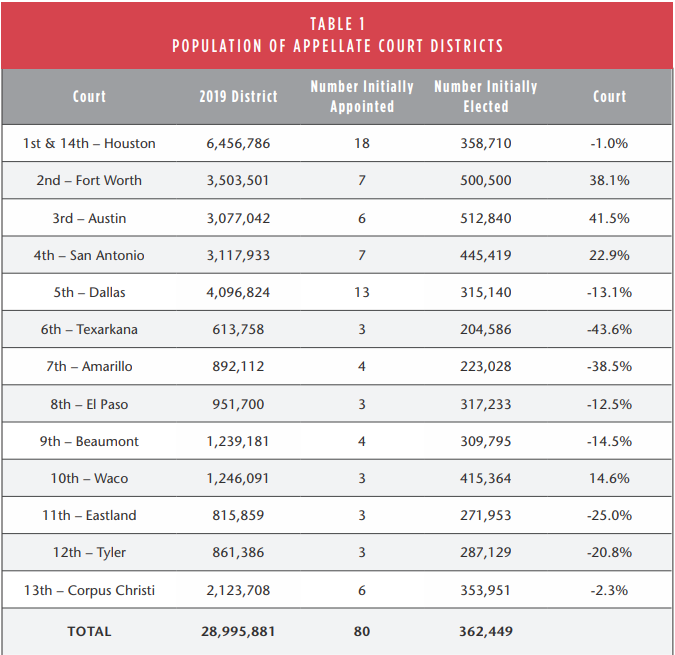

History of Texas’s Intermediate Appellate Courts. The 1876 Texas Constitution provided for a three-judge court of appeals having civil and criminal jurisdiction.89 The 1891 constitutional amendments required the Legislature to divide Texas into “supreme judicial districts” with a court of civil appeals in each district.90 It provided that each court of civil appeals was to consist of a chief justice and two associate judges.91 These intermediate appellate courts did not have criminal jurisdiction. The Legislature established five courts of civil appeals, in Galveston, Fort Worth, Austin, San Antonio, and Dallas. Over the next seventy five years, the Legislature established additional three-justice courts of civil appeals as caseload demanded. The following Table 1 shows the year each court of civil appeals was established.

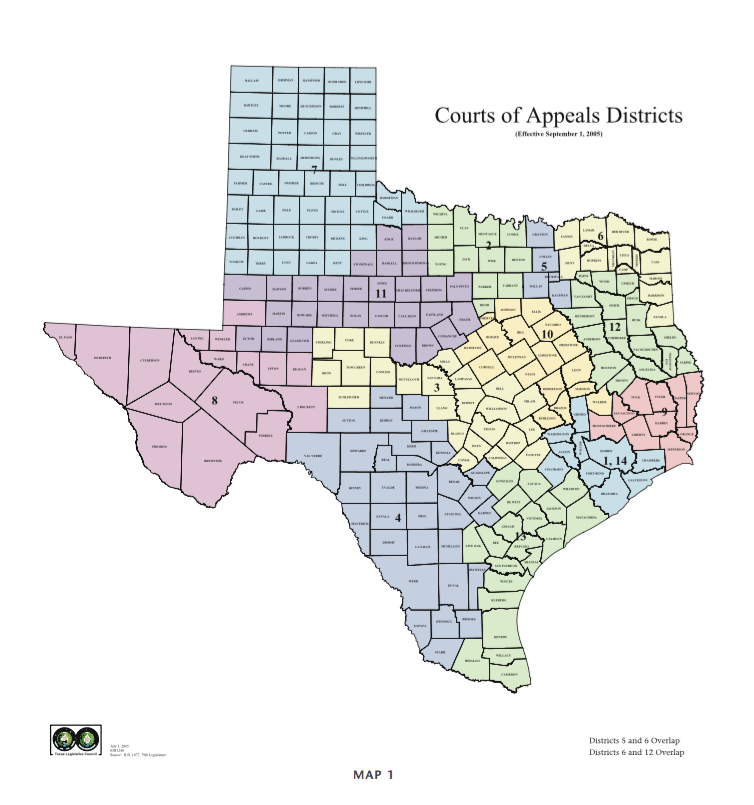

The history of the courts of appeals explains how Texas ended up as the only state with overlapping intermediate appellate court districts.94 In 1927, the Legislature transferred Hunt County from the Dallas Court of Appeals district to the Texarkana Court of Appeals’ district.95 Seven years later, it restored Hunt County to the Dallas court’s district, but did not remove it from the Texarkana court’s district, thus creating the first instance of overlapping court of appeals districts.96 In 1963, the Legislature established the seventeen-county Tyler Court of Appeals.97 Nine of the counties comprising the new district were removed from their former districts, but the other eight remained in their previous districts.98 Consequently, Gregg, Hopkins, Panola, Rusk, Upshur and Wood Counties were in the Texarkana and Tyler courts’ districts, and Kaufman and Van Zandt Counties were in the Dallas and Tyler courts’ districts.99 Texas now had nine counties that were within two intermediate appellate court districts.

TABLE 1

In 1967, the Legislature established the Fourteenth Court of Appeals in Houston, covering the same counties as the existing First Court of Appeals.100 In addition to the thirteen counties already covered by the First Court of Appeals, the Legislature added Brazos County to both Houston courts’ districts, while leaving it in the Waco Court of Appeals’ district as well.101 Brazos County, therefore, was within three courts of appeals’ districts. Thus, by 1967, twenty-two Texas counties were in two intermediate appellate court districts, and one county was in three.

In 1978, an amendment to the Texas Constitution allowed the Legislature to expand the number of justices on the courts of appeals. This allowed the Legislature to address increases in the intermediate appellate courts’ workload without further increasing the number of courts of appeals.102

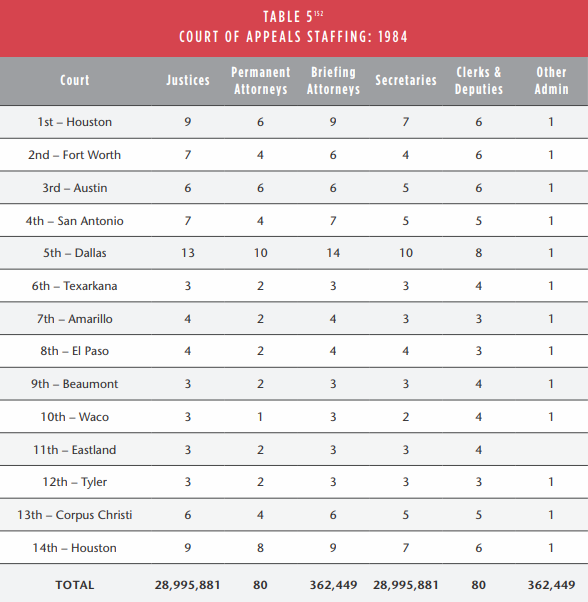

In 1981, the constitution was amended to give the intermediate courts of appeals criminal jurisdiction except in death penalty cases and to change the name of those courts from “courts of civil appeals” to “courts of appeals.”103 A number of judges were added to the courts of appeals to handle the additional caseload.104

In 2003, the Legislature began to untangle the courts of appeals’ overlapping districts by removing Brazos County from the two Houston courts’ districts and leaving it in the Waco court’s district.105 The Legislature also began reapportioning the districts, by moving Ector, Gaines, Glasscock, Martin and Midland counties from the El Paso court’s district to the Eastland court’s district.106 And it reduced the size of the El Paso court from four to three justices, and increased the size of the Beaumont court from three to four justices.107

In 2005, the Legislature continued its effort to untangle and reapportion the courts of appeals.108 It removed Burleson, Trinity and Walker Counties from the two Houston courts’ districts, putting Burleson and Walker Counties in the Waco court’s district and Trinity County in the Tyler court’s district. It also took Van Zandt County out of the Dallas court’s district, leaving it in the Tyler court’s district. It moved Angelina County from the Beaumont court’s district to the Tyler court’s district, and took Hopkins, Kaufman and Panola Counties out of the Tyler court’s district, leaving Hopkins and Panola in the Texarkana court’s district and Kaufman in the Dallas court’s district.

Today, five counties in northeast Texas (Gregg, Hunt, Rusk, Upshur, and Wood) remain in two courts of appeals districts109 and the two Houston court districts, consisting of ten counties, are entirely overlapping.110 No county is in three districts anymore.

Courts of Appeals Today

Judges and Districts. Since 1967, Texas has had fourteen intermediate courts of appeals.111 Today, those courts have a total of eighty justices.112 The largest court has thirteen justices and the smallest courts have three.113 A court of appeals’ justice must have the same qualifications as a Texas Supreme Court justice.114 A vacancy on a court of appeals is filled by gubernatorial appointment with the consent of the Senate unil the next general election.115

The two Houston Courts of Appeals have established a central clerk’s office and central offices for the eighteen justices and other support personnel.116 The clerks of the two courts will periodically equalize the dockets of the two courts by transferring cases from one to the other.117 Initially, cases are randomly assigned between the two courts.118

The Dallas and Texarkana courts share Hunt County,119 and the Texarkana and Tyler courts share Gregg, Rusk, Upshur, and Wood Counties.120 There is no system for the random assignment of appeals from these counties to the two available courts of appeals. Consequently, the appealing party chooses the court of appeals.121 If more than one party wishes to appeal, there may be a “race to the courthouse” because the appellate court that first acquires jurisdiction is dominant and any other court of appeals in which an appeal has been lodged must abate the appeal.122

Jurisdiction. In civil cases, each court of appeals has appellate jurisdiction of those civil cases arising from within its district of which the district or county courts have jurisdiction when the amount in controversy or judgment rendered exceeds

$100.123 Their jurisdiction includes jurisdiction of appeals arising from final judgments and interlocutory trial court orders made appealable by statute.124 The courts have criminal appellate jurisdiction coextensive with the limits of their respective districts in all criminal cases except those cases in which the death penalty has been assessed.125 Death penalty cases bypass the courts of appeals and go directly to the Court of Criminal Appeals.126

Workload. The courts typically hear argument and decide cases in three-judge panels, although the courts may be convened en banc to hear and decide cases.127 If a court has more than three justices so that more than one panel is used, the court must establish rules to rotate the justices among the panels.128 A majority of a panel constitutes a quorum, and the concurrence of a majority of a panel is necessary for a decision.129 For business other than “hearing cases,” the Chief Justice of the court of appeals must convene the court en banc.130

MAP 1

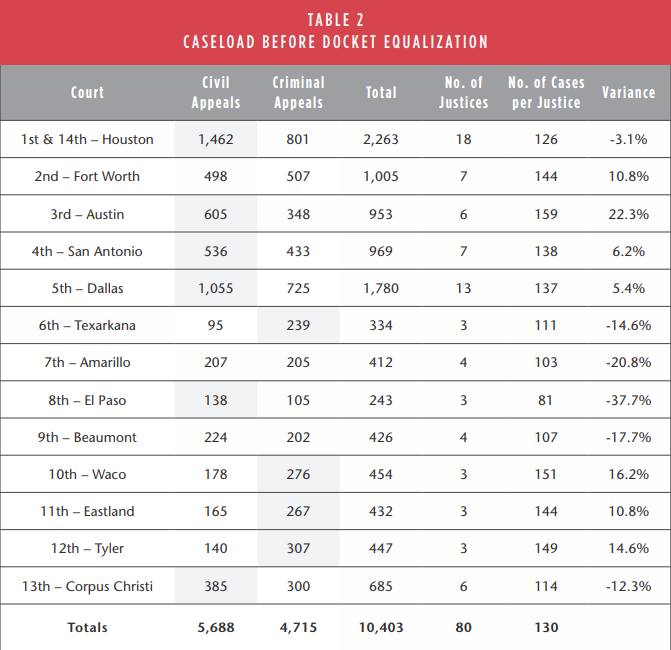

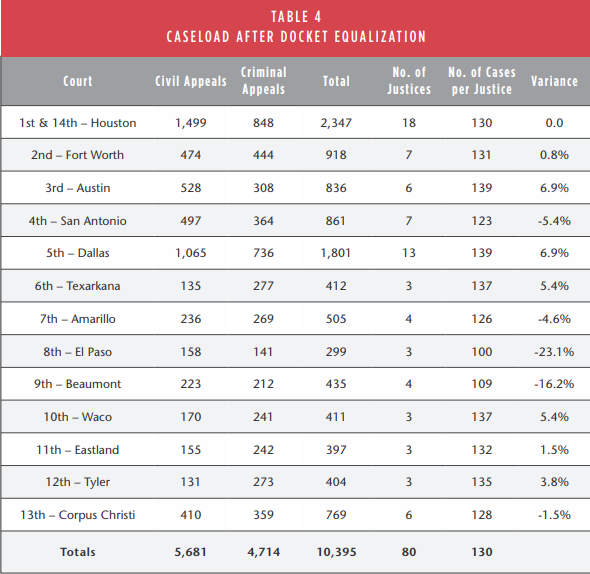

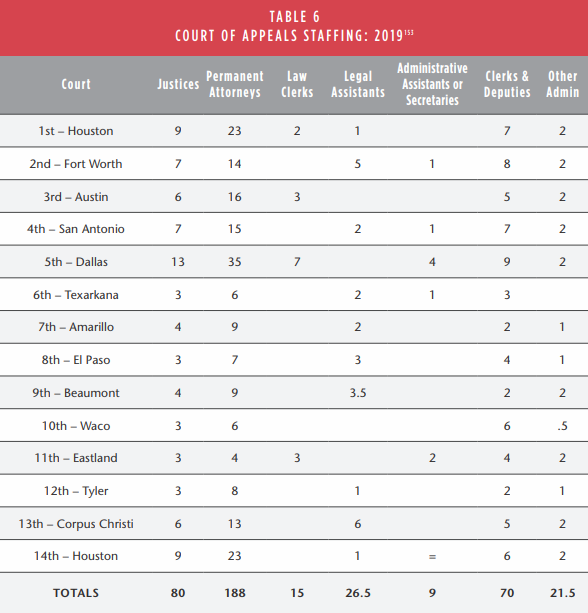

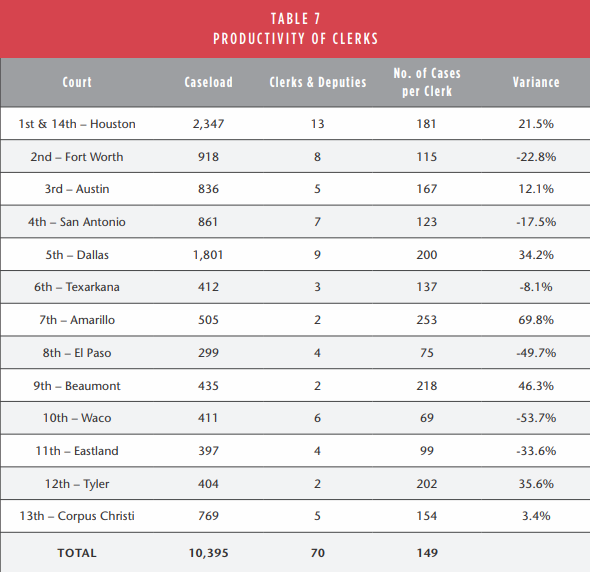

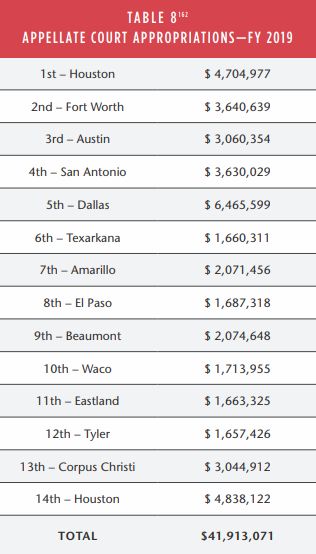

Collectively, over the past ten years, 5161 civil cases and 6808 criminal cases have been added to the fourteen courts of appeals dockets each year, on average.131 The courts write an average of 11,635 opinions per year, or 145 opinions per judge.132 Because of variations in population and litigation activity, there is a disparity between the numbers of cases filed in each court on a per-judge basis. Table 2 reflects new filings per-judge for fiscal year 2005.133

TABLE 2

These statistics show that, with the exception of the Beaumont and Corpus Christi courts, the courts with six or more justices are receiving more new cases each year on a per-judge basis than the courts with fewer justices.

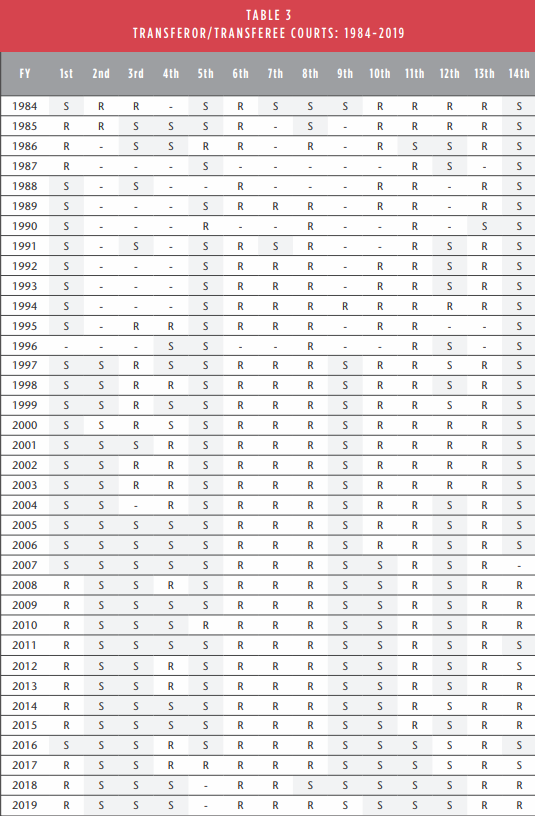

The Supreme Court has authority to transfer cases among the courts at any time there is good cause for the transfer.134 At the Legislature’s behest accomplished by a rider on the annual appropriations bill,135 the Supreme Court uses this authority to transfer cases to equalize the courts of appeals’ dockets.136 As Table 3 shows, in 2005 the Houston, Fort Worth, Austin, San Antonio, Dallas, Beaumont and Tyler courts of appeals were net transferors of cases, while the Texarkana, Amarillo, El Paso, Waco, Eastland and Corpus Christi courts were net transferees.

TABLE 3

According to the Office of Court Administration (OCA), 561 cases were transferred into a court of appeals and 572 were transferred out of a court of appeals in fiscal year 2005.138 Thus, about 5.5% of the 10,394 new cases filed in the courts of appeals in fiscal year 2005 were transferred from one court of appeals to another.

Trial Courts

1876 Trial Court Structure. In 1876, when the current constitution was adopted, Texas had a three-tier trial court structure consisting of justice of the peace courts, county courts, and district courts.139 Justice courts operated in precincts within each county. No special qualifications were required to be a justice of the peace. The justice courts had jurisdiction in criminal cases in which a fine of $200 or less could be imposed and in civil matters in which the amount in controversy was $200 or less. A justice court judgment, except one below $20, could be appealed to the county court.140

Every county had a county court.141 A county judge had to be “well informed in the law of the State,” but did not have to be an attorney.142 County courts had jurisdiction of all mis-demeanors, except those in which the fine imposed could not exceed $200.143 In civil matters, county courts had exclusive jurisdiction of cases in which the amount in controversy exceeded $200, but did not exceed $500, and concurrent jurisdiction with the district courts when the amount was from $500 to $1000.144 A county court’s judgment in a civil matter could be appealed to the court of appeals.145 County courts also had probate jurisdiction, and a county court’s judgment in a probate matter could be appealed to a district court.146

TABLE 4

At the top of the trial court pyramid were the district courts. A district judge had to be an experienced attorney.147 The district courts had criminal jurisdiction of felonies, civil jurisdiction of matters with an amount in controversy of $500 or more, and appellate jurisdiction of probate matters originating in the county courts.148 A district court’s judgment could be appealed to an appellate court.149

There was no overlapping subject-matter jurisdiction between justice courts and county courts or district courts. The only overlapping jurisdiction between county courts and district courts involved civil cases with an amount in controversy between $500 and $1000. And if the amount in controversy in a civil case was too small, an appeal was not permitted. Significant cases were handled by the highest trial courts, sitting in multi-county districts, whose judges were attorneys.

Today’s Byzantine Trial Court Structure. Today, as depicted in Table 5, Texas has seven types of trial courts—district courts, statutory county courts (called county courts at law), statutory probate courts, constitutional county courts, justice of the peace courts, small claims courts, and municipal courts.150 The subject-matter jurisdiction of almost every type of trial court overlaps in at least one way with the subject-matter jurisdiction of every other type of trial court.151 Additionally, the subject-matter jurisdiction of constitutional county courts varies widely from county to county, as does the subject-matter jurisdiction of statutory county courts.152 According to Texas Supreme Court Justice Nathan Hecht in a recent opinion, “[t]he jurisdictional structure of the Texas court system is unimaginably abstruse.”153 Over the years, the jurisdictional scheme “has gone from elaborate…to Byzantine.”154

In addition to having a highly complicated jurisdictional scheme, the geographic structure of Texas’s district court system creates a spider web of overlapping districts.155 A single county may be in three or four unique districts.156 A number of district courts sit in two appellate court districts, and two district courts sit in four appellate court districts.157 Several district courts also sit in two regional administrative districts.158 And the administrative regions do not match the intermediate appellate court districts.159

When the byzantine jurisdictional structure is coupled with the spider web of overlapping districts, the variations become overwhelming.

The OCA’s detailed description of Texas trial court structure and jurisdiction comprises seventeen pages of fine print.160 In a nutshell, Texas’s trial court structure is antiquated and tangled, and it verges on irrational.

TABLE 5

- Arguably, small claims courts do not have jurisdiction of claims below $200.

- JP court jurisdiction is limited to $5000 except in eviction cases, in which there is no limit.

- Some constitutional county courts have been stripped of civil jurisdiction.

- Probate courts can hear survival actions, wrongful death claims, and other actions incident to an estate without regard to the amount in controversy.

- Most county courts at law are limited to cases with < $100,000 in controversy, but some have unlimited civil jurisdiction.

- The lower limit of district court jurisdiction is unclear. It could be $200, $500 or $5000.

District Courts

Number of Courts and Qualification of Judges. The Texas Constitution provides that “[t]he judicial power of this State shall be vested…in District Courts” and that the State must “be divided into judicial districts, with each district having one or more Judges as may be provided by law or by this Constitution.”161 The Texas Legislature has authorized 438 district courts.162 Six of these came into existence on January 1, 2007.163

To be eligible to serve as a district judge, a person must: (1) be at least 25 years of age, (2) be a citizen of the United States and of Texas, (3) be licensed to practice law in Texas, (4) have been a practicing lawyer or a judge of a Texas court, or both combined, for four years preceding the election, and (5) have resided in the district in which he or she is elected for two years preceding the election.164 A district judge must reside in the district during the term of office.165 District judges are “elected by the qualified voters at a General Election” to four-year terms.166 When a vacancy occurs on a district court, the vacancy is filled by gubernatorial appointment, with the consent of the Senate, until the next succeeding general election.167

Jurisdiction. In civil matters, Texas’s district courts are courts of general original jurisdiction, entertaining every kind of legal and equitable claim.168 The Texas Constitution provides that the district courts have exclusive, appellate, and original jurisdiction of all actions, proceedings, and remedies, except in cases where exclusive, appellate, or original jurisdiction may be conferred by the constitution or other law on some other court, tribunal, or administrative body.169 They are empowered to hear and determine any cause cognizable by courts of law or equity and may grant relief that could be granted by courts of law or equity.170

* The lower monetary limit is uncertain. It could be $200, $500, or $5000, depending on how the constitution and statutes are interpreted.

TABLE 6

Neither the current constitution nor any statute provides a minimum amount in controversy necessary to confer district court jurisdiction. Instead, the constitution provides that district courts do not have jurisdiction if “exclusive, appellate, or original jurisdiction” has been conferred on another court “by this Constitution or other law.”171 Because justice courts have exclusive jurisdiction of civil cases in which the amount in controversy is $200 or less,172 the lower monetary limit of district court jurisdiction appears to be $200.173 There is no upper monetary limit to district court jurisdiction.

In criminal matters, district courts have original jurisdiction of all felonies, of misdemeanors involving official misconduct, and of misdemeanors punishable with jail time if the case is transferred to the district court, with the written consent of the district judge, from a county court with a non-lawyer as a judge.174

Some of Texas’s district courts could be regarded as specialized courts. The Texas Government Code establishes “Family District Courts” with the same jurisdiction and power provided for district courts by the Texas Constitution and the Government Code, but with primary responsibility for family matters.175 In other words, the Legislature has established district courts, given them primary responsibility for some kinds of cases, but has not limited their jurisdiction. The Government Code also provides for criminal district courts in Dallas, Tarrant, and Jefferson Counties.176 These courts are district-level courts but are not, strictly speaking, district courts. They are “other courts” established by the Legislature under Article V, § 1 of the constitution, and have limited jurisdiction. Additionally, the Government Code provides that any district court has jurisdiction over juvenile matters and “may be designated a juvenile court.”177 Finally, the Legislature has established and empowered a multidistrict litigation procedure by which related cases can be consolidated in a single district court for pretrial proceedings, effectively creating courts that are specialized in particular kinds of cases like asbestos or silica litigation.178

Districts and Reapportioning Districts. Many of Texas’s district courts have a multicounty district, while many Texas counties have multiple district courts sitting only in that county.179 In any county with two or more district courts, the judges of those courts may transfer any civil or criminal case to one of the other district courts in the county.180 In addition, the judges of these courts may, in their discretion, sit for another district judge in that county.181

As shown on Map 2, some counties are in more than one district court district with differing sets of neighboring counties. For example, Anderson County is in the 87th District with Freestone, Leon, and Limestone Counties, in the 3rd District with Henderson and Houston Counties, in the 349th District with Houston County, and in the 369th District with Cherokee County.182 These overlapping districts are most common in East Texas, but are found in other parts of the State as well.183

To make matters more complicated, court of appeals districts have little correlation to district court districts. As a result, district judges often answer to two or more courts of appeals. For example, rulings made by the judge of the 87th District Court when he or she is sitting in Freestone, Leon, or Limestone Counties are reviewed by the Waco Court of Appeals, but rulings he or she makes while sitting in Anderson County are reviewed by the Tyler Court of Appeals.184 Two Texas district judges answer to four courts of appeals.185 This can be a significant problem when the courts of appeals differ on an important issue of law, which may remain unresolved for years until the Texas Supreme Court or Court of Criminal Appeals resolves the conflict.186

Finally, several multi-county district courts are in two administrative regions. For example, the 155th District Court is in both the Second and Third administrative regions, the 198th District Court is in both the Sixth and Seventh administrative regions, and the 273rd District Court is in both the First and Second administrative regions.187

All of these problems could be addressed through the reapportionment of district court districts. Article V, § 7a of the Texas Constitution establishes the “Judicial Districts Board” for the purpose of reapportioning the district courts’ judicial districts.188 The Chief Justice of the Texas Supreme Court serves as chairman of the Judicial Districts Board.189 The other members of the Board are the Presiding Judge of the Court of Criminal Appeals, the presiding judge of each of the administrative judicial districts of the state, the president of the Texas Judicial Council, and one Texas lawyer appointed by the Governor with the advice and consent of the Senate.190

The constitution requires the Board to “convene not later than the first Monday of June of the third year following the year in which the federal decennial census is taken to make a statewide reapportionment of the districts” “[u]nless the Legislature enacts a statewide reapportionment of the judicial districts following [the] federal decennial census.”191 If the Judicial Districts Board fails to make a statewide reapportionment by August 31 of the year it commences its work, “the Legislative Redistricting Board established by Article III, Section 28, of this constitution shall make a statewide reapportionment of the judicial districts not later than the 150th day after the final day for the Judicial Districts Board to make the reapportionment.”192

The Board is specifically empowered to redesignate the county or counties that comprise the specific judicial districts affected by its reapportionment orders.193 Finally, “[A]ny judicial reapportionment order adopted by the board must be approved by a record vote of the majority of the membership of both the senate and house of representatives before such order can become effective and binding.”194 Two decennial censuses have been conducted since the adoption of Article V, § 7a in 1985, but the Legislature, the Judicial Districts Board, and the Legislative Redistricting Board have not conducted the judicial reapportionment required by § 7a after either census.

Workload. In fiscal year 2005, over 263,000 criminal cases were added to the district courts’ dockets.195 The district courts disposed of almost 257,000 criminal cases in fiscal year 2005, leaving almost 229,000 criminal cases pending.196 About 613,000 civil matters were filed in the district courts in fiscal year 2005, about 124,000 of which involved show cause motions.197 The courts disposed of almost 546,000 civil cases, leaving more than 666,000 civil cases pending.198

MAP 2

County-Level Courts

Statutory County Courts (County Courts at Law). Article V, § 1 of the Texas Constitution allows the Legislature to establish such other courts as it deems necessary and to prescribe the jurisdiction of those courts. In exercising this power, the Legislature in 1907 began establishing statutory county courts (commonly called county courts at law), the first of which was established in Dallas County.199 By 1953, there were eighteen county courts at law sitting in thirteen counties.200 All had the same jurisdictional limit on monetary claims as were applicable to the constitutional county courts—they could hear claims for damages from $200 to $500.201

Today, there are 217 county courts at law located in eighty-four of Texas’s 254 counties.202

* Many statutes specific to individual counties expand the upper monetary limit in civil cases.

** Specific statutes often give County Court at Law jurisdiction of some of these types of cases, particularly divorce cases.* Many statutes specific to individual counties expand the upper monetary limit in civil cases.

TABLE 7

Unlike district courts, which have jurisdiction of “all actions, proceedings and remedies”203 (meaning that district courts have jurisdiction of, among others, family law cases and cases in which equitable relief is sought), the county courts at law have only the specific jurisdiction conferred on them by statute. In other words, with exceptions we will describe below, these are courts of limited jurisdiction.

The jurisdiction statute generally applicable to the county courts at law provides that these courts have jurisdiction over “all causes and proceedings, civil and criminal, original and appellate, prescribed by law for [constitutional] county courts.”204 Constitutional county courts—and, therefore, county courts at law—have original jurisdiction of “all misdemeanors of which exclusive original jurisdiction is not given to the justice court, and when the fine to be imposed shall exceed five hundred dollars,” and appellate jurisdiction in criminal cases of which justice courts and other inferior courts have original jurisdiction.205

In civil cases, constitutional county courts—and, therefore, county courts at law— have jurisdiction to hear and determine any cause in law or equity that a court of law or equity recognizes and may grant any relief that may be granted by a court of law or equity.206 They have jurisdiction when the amount in controversy exceeds $200 but does not exceed $5000 and appellate jurisdiction in civil cases over which the justice courts have original jurisdiction, if the judgment or amount in controversy exceeds $20.207 They do not have jurisdiction of, among other cases:

- suits to recover damages for slander or defamation of character, (2) suits for the enforcement of a lien on land, (3) suits for divorce, (4) suits for the forfeiture of a corporate charter, or (5) eminent domain cases.208

The $5000 upper monetary limit applicable to constitutional county courts, however, actually does not apply to county courts at law because the generally applicable jurisdiction statute for county courts at law provides that they have jurisdiction concurrent with the district court in civil cases in which the matter in controversy exceeds $500 but does not exceed $100,000.209 Consequently, county court at law monetary jurisdiction is from $200 to $100,000 unless lesser or greater jurisdiction is provided by another statute for an individual court.

County courts at law also have jurisdiction of appeals of final decisions of the Texas Department of Insurance regarding workers’ compensation claims, regardless of the amount in controversy, and the probate jurisdiction provided by general law for constitutional county courts.210

However, because each county court at law is established by a specific statute and the constitution allows the Legislature to set the jurisdiction of courts established by statute, many county courts at law have specific jurisdiction statutes giving them jurisdiction that is greater than that provided by the generally applicable statute.211 As a result, county court at law jurisdiction varies significantly from county to county. In fourteen counties, for example, the county courts at law have concurrent jurisdiction with district courts in all civil cases. Therefore, no upper monetary limit is applicable to those courts and they have jurisdiction of several types of cases, like divorce and defamation cases, that county courts at law in other counties cannot hear.212 In still other counties, the county courts at law are given specific jurisdiction—for example, family law jurisdiction or jurisdiction of felony cases.213

Even though statutory county courts at law have overlapping jurisdiction with state district courts, and many of them have limitless jurisdiction, as described in the preceding paragraph, only six jurors serve in a case tried in a county court at law.214 If the same case were tried in district court, twelve jurors would serve.215 This feature can cause litigants to decide that one court or the other is a better choice in a given case. The courts should not be structured in a way that encourages shopping for a favorable forum.

In a county with a statutory probate court, the probate court is the only statutory county-level court with probate jurisdiction.216 In counties that do not have a statutory probate court, a statutory county court (concurrent with the constitutional county court) has probate jurisdiction as provided by law for constitutional county courts.217

To serve as a county court at law judge, a person must: (1) be at least 25 years of age, (2) have resided in the county in which the court sits for at least two years before election or appointment, (3) be a licensed Texas attorney, and (4) have practiced law or served as a Texas state-court judge, or both combined, for the four years preceding election or appointment.218 When a vacancy occurs on a county court at law, it is filled by a person appointed by the commissioners court of the county in which the court sits, not by the governor as would be a district court vacancy.219 The appointee holds office until the next general election and until his or her successor is elected and qualified.220

Statutory Probate Courts. There are seventeen statutory probate courts in Texas. Again, these courts have been created pursuant to the Legislature’s authority under the constitution to create such courts as it deems necessary.221 Statutory probate courts sit in Bexar, Dallas, Denton, El Paso, Galveston, Harris, Hidalgo, Tarrant and Travis Counties.222 The qualifications for serving as a statutory probate court judge are the same as those for a county court at law judge.223

TABLE 8

The Government Code provides that statutory probate courts have “the general jurisdiction of a probate court as provided by the Texas Probate Code.”224 Statutory probate courts also have the jurisdiction provided by law for a county court to hear and determine other miscellaneous actions, such as a proceeding to establish a record of a person’s date of birth, place of birth, and parentage instituted under §192.027 of the Health and Safety Code.225

For those counties in which there is a statutory probate court, “all applications, petitions, and motions regarding probate or administrations shall be filed and heard in the statutory probate court.”226 A parallel provision requires that “all applications, petitions, and motions regarding guardianships, mental health matters, or other matters addressed by this chapter [of the Probate Code] shall be filed and heard in the statutory probate court.”227

A statutory probate court also has concurrent jurisdiction with the district court “in all personal injury, survival, or wrongful death actions by or against a person in the person’s capacity as a personal representative, in all actions by or against a trustee, in all actions involving an inter vivos trust, testamentary trust, or charitable trust, and in all actions involving a personal representative of an estate in which each other party aligned with the personal representative is not an interested person in that estate.”228 Similarly, a statutory probate court “has concurrent jurisdiction with the district court in all personal injury, survival, or wrongful death actions by or against a person in the person’s capacity as a guardian and in all actions involving a guardian in which each other party aligned with the guardian is not an interested person in the guardianship.”229

All courts exercising original probate jurisdiction have the power to hear all matters “incident to” a probate or guardianship estate.230 Statutory probate courts have jurisdiction over any matter “appertaining to” or “incident to” a probate or guardianship estate and have jurisdiction over any cause of action in which a personal representative or guardian is a party in a proceeding pending in the statutory probate court.”231 The phrases “appertaining to estates” and “incident to an estate” include the probate of wills, issuance of letters testamentary and of administration, determination of heirship, appointment of guardians, and issuance of letters of guardianship.232 The terms cover all claims by or against a probate or guardianship estate,233 all actions for trial of title to land and for the enforcement of liens thereon,234 all actions for the trial of the right of property,235 all actions to construe wills,236 interpretation and administration of testamentary trusts and the application of constructive trusts,237 and, generally, all matters relating to the collection, settlement, partition, and distribution of estates of deceased persons or guardianship estates.238

Finally, a statutory probate court, in either a probate or guardianship matter, “may exercise the pendent and ancillary jurisdiction necessary to promote judicial efficiency and economy.”239 The purpose of pendent and ancillary jurisdiction is to permit the hearing of tangentially related cases if hearing those cases would promote judicial economy.240 Probate courts generally exercise ancillary or pendent jurisdiction over non-probate matters only when doing so will aid in the efficient administration of an estate pending in the probate court.241

The Probate Code provides that “[a] judge of a statutory probate court…may transfer to his court from a district, county, or statutory court a cause of action appertaining to or incident to an estate pending in the statutory probate court or a cause of action in which a personal representative of an estate pending in the statutory probate court is a party.”242 Another section of the Probate Code gives probate court judges the ability to transfer from a district, county or statutory court causes of action “appertaining to or incident to a guardianship estate that is pending in the statutory probate court.”243 Transfer of proceedings to the statutory probate court is permissive and not mandatory.244 Thus, a probate court may transfer to itself a cause of action that is appertaining to or incident to an estate, but is not required to do so.245 A probate court’s ability to transfer actions to itself is not unlimited, however. A statutory probate court cannot transfer a case to itself if venue in the county of the statutory probate court is improper under Civil Practice and Remedies Code § 15.007.246

If the judge of a statutory probate court having jurisdiction over a cause of action appertaining to or incident to an estate pending in the statutory probate court determines that the court no longer has jurisdiction over the cause of action, the judge may transfer that cause of action to (1) a district court, county court, statutory county court, or justice court located in the same county having jurisdiction over the cause of action, or (2) the court from which the cause of action was transferred to the statutory probate court pursuant to Probate Code §§ 5B or 608.247

Constitutional County Courts. The 1836 constitution provided for a county court in each county.248 The 1845 and 1861 constitutions did not, but they required instead that the Legislature establish “inferior tribunals…in each county for appointing guardians, granting letters testamentary and of administration; for settling the accounts of executors, administrators, and guardians, and for the transaction of business appertaining to estates.”249

TABLE 9

The 1866 constitution again provided for the establishment of a county court in each county and for the election of a county judge.250 The county court was given jurisdiction of “misdemeanors and petty offences” and of civil cases in which the amount in controversy did not exceed $500.251 This created an overlap with district court jurisdiction, which at that time, involved any case in which the amount in controversy was $100 or more.252 The county courts also were given power to, among other things, probate wills, appoint guardians, and grant letters testamentary.253 The 1866 constitution also called for the selection of four county commissioners who, along with the county judge, constituted the “Police Court for the County.”254 The Police Court was not a judicial body, but was charged with regulating, promoting, and protecting the county’s public interest.255

The 1869 constitution did not provide for county judges or a Police Court. Instead, it required that each county elect five justices of the peace who, in addition to their judicial duties, would have “such jurisdiction, similar to that heretofore exercised by county commissioners and police courts.”256

The current constitution (adopted in 1876) provides that Texas’s judicial power is vested in, among others, county courts and commissioners courts.257 It established a county court in all of Texas’s 254 counties.258 The district courts initially had appellate jurisdiction and “general control in probate matters” over the county courts.259 The county courts were given original jurisdiction of misdemeanors unless exclusive original jurisdiction rested in the justice of the peace courts, concurrent jurisdiction with the justice courts in civil cases when the matter in controversy exceeded

$200 but did not exceed $500, and concurrent jurisdiction with the district courts when the matter in controversy was between $500 and $1000. In addition, they were given appellate jurisdiction in cases in which the justice of the peace courts had original jurisdiction if the judgment exceeded $20, and the power to probate wills, “appoint guardians of minors, idiots, lunatics, persons non compos mentis and common drunkards,” and to grant letters testamentary and of administration.260 The county judge also presides over a four-member commissioners court in each county, which has “powers and jurisdiction over all county business.”261

The constitution was amended in 1985, and the section governing county court jurisdiction was revised to provide that the county courts have “jurisdiction as provided by law” and that a county judge is the “presiding officer of the County Court and has judicial functions as provided by law.”262 Consequently, while constitutional county courts are established in the constitution, the jurisdiction of those courts is now provided by statute, not by the constitution.

The Government Code gives constitutional county courts jurisdiction to hear and determine any cause in law or equity that a court of law or equity recognizes and may grant any relief that may be granted by a court of law or equity.263 Unless another statute provides differently, these courts have jurisdiction of civil cases in which the amount in controversy exceeds $200 but does not exceed $5000, and appellate jurisdiction in civil cases over which the justice courts had original jurisdiction if the judgment or amount in controversy exceeds $20.264 Constitutional county courts do not have jurisdiction, among other cases, in: (1) suits to recover damages for slander or defamation of character, (2) suits for the enforcement of a lien on land, (3) suits for divorce, (4) suits for the forfeiture of a corporate charter, or (5) eminent domain cases.265

The Probate Code provides that constitutional county courts have “the general jurisdiction of a probate court” and are empowered to “probate wills, grant letters testamentary and of administration, settle accounts of personal representatives, and transact all business appertaining to estates subject to administration, including the settlement, partition, and distribution of such estates.”266 In those counties in which there is no statutory probate court or county court at law, all applications, petitions, and motions regarding probate and administrations must be filed and heard in the county court.267 If a contested matter arises in the probate proceeding, the judge of the county court may on the judge’s own motion or shall on the motion of a party, request the assignment of a statutory probate court judge to hear the contested portion of the proceeding or transfer the contested portion of the proceeding to the district court, which hears the contested matter as if it had been originally filed in district court.268

In those counties in which there is no statutory probate court, but in which there is a county court at law, “all applications, petitions, and motions regarding probate and administrations shall be filed and heard in those courts and the constitutional county court, unless otherwise provided by law.”269 If a contested matter arises in the probate case, the judge of the constitutional county court may on the judge’s own motion, and shall on the motion of a party, transfer the proceeding to the county court at law, which hears the proceeding as if it had been originally filed in that court.270

In criminal cases, the constitutional county courts have original jurisdiction of “all misdemeanors of which exclusive original jurisdiction is not given to the justice court, and when the fine to be imposed shall exceed five hundred dollars,” and appellate jurisdiction in criminal cases of which justice courts and other inferior courts have original jurisdiction.271 If the county court’s jurisdiction has been transferred by statute to a district or statutory county court, then an appeal in a criminal case from a justice or other inferior court is to the court to which the county court’s jurisdiction has been transferred.272